by Stephanie Block

It’s that time of year again, to say good-bye to good, old 5764 and welcome 5765. It’s the Jewish New Year! The Jewish calendar is a little bit at odds with the Gregorians of the world- it leans lunar, so each year we have to chase down our dates and match them up. And speaking of the order of things, we celebrate first, much like a lot of folks, and then spend days filled with guilt, regret, and apologies. Like a serious spiritual hangover.

In a sense, the Jewish New Year is like that Auld Lang Syne night of champagne and midnight kisses. In both cases, resolutions are made with great aplomb and well, sort of peter out. It’s because of this very human trait, the fact that we promise the world but usually fall short, that our Jewish New Year is such a complicated process that stretches over ten days. In those ten days, we take the time to face our shortcomings: the promises we made and failed to keep with ourselves and with our loved ones and friends, and ultimately, the promises we broke with G-d. We call these the High Holy Days. Our celebration starts out joyously enough, when we eat apples dipped in honey to ensure a sweet New Year, and ends quite soberly on Yom Kippur, which is our Day of Atonement.

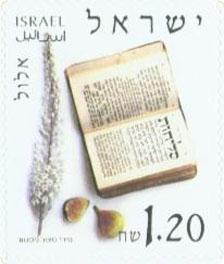

During the time between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we do the hard work of reflecting back over the last year. Why? Because G-d has been keeping track of who has been naughty and nice. For us, though, there is way more at stake than whether or not we get the Barbie Dream House. Our ledger is the Book of Life, and we are up for review every year. By the time Rosh Hashanah comes around, Fate is pretty much sealed, but not quite. Within the ten holy days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, attempts we make to right our wrongs are duly noted. We have a saying, On Rosh Hashanah it is written; on Yom Kippur it is sealed. We want our names written and sealed in the Book of Life for another year.

Maybe it’s only mythology, but the Book of Life has always felt very real and scary to me. I guess as a writer, the threat of being unpublished hits pretty close to home. Like a lot of other people, I don’t usually go to Temple. But I rarely miss Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services- it’s three parts guilt from my mother and one part fear of death, that I really will be struck by lightning the very minute the sun goes down on Yom Kippur if I don’t go and recite at least some of the blessings. Our rabbi at Beth Sholom always makes little comments about how nice it was of us all to show up and where were we last Friday night and so on.

Every year, my mom gets us up early so that we can get a good parking spot at Beth Sholom, and so that we have enough time to change if she doesn’t approve of our outfits. My chances at the Book of Life would be pretty slim if my skirt were too short. Our temple even issues tickets to the High Holy Days, which do, in fact, sell out. We’re supposed to miss school and work, which sounds fantastic until you realize you’ll just be getting dressed up to go sit someplace else that’s kind of boring.

Food, of course, is at the heart of these occasions. On Rosh Hashanah, we eat many traditional, sweet dishes like honey cake and a special, round challah bread with raisins in it, kugel (sweet noodle casserole), and tzimmis (sweet stew). Then, on Yom Kippur, to punctuate our penance, we fast the entire day. We neither eat nor drink until sunset. Of course, if you are on medication or are frail, you are allowed forego the fast. At sunset, we have what are called Break the Fast parties, where families and friends with low blood sugars and grumbling tummies get together to break our day long fast and celebrate the New Year and our place in it.

As in, after looking around nervously all day for open manholes and falling pianos, we tentatively whisper, phew, I think I’m in!

Jewish holidays are filled with rituals and mysticism. One very important High Holy Days decree that we follow is the blowing of the shofar. This is a very special, sacred component of the services. The way I remember it, an official person, a ba’al toke’a, comes onto the stage, or bema, and blows the shofar in response to the rabbi’s commands. This person wears long robes and holds a beautifully twisting, noble ram’s horn in his hands. He puts the long horn to his lips and suddenly, the quiet synagogue is filled with a rich, ethereal series of blasts like a beacon or call to prayer. Scholars say it also serves to remind us of the time G-d asked Abraham to sacrifice his only son as proof of his devotion, one of history’s ultimate promises made, kept, and rewarded.

So if you are Jewish or have Jewish friends, don’t forget to wish celebrants a happy L’shanah tova, which is the short version of, may you be inscribed and sealed for a good year. Too, forgive each other for any wrongs committed during the previous year to ensure all our places in the good Book. At the end of the day, may we all be best sellers!